Wing IDE Professional

Implementation and Feature Tour

The presentation starts on the next slide.

To adjust font size use ctrl +/- or command +/- on OS X; arrow keys and space bar move through the slides; mouse over lower right to view the slides with notes or jump to a page.

This presentation was developed with S5

Wing IDE Professional

Implementation and Feature Tour

Wingware.com

Hi. My name is Stephan Deibel, and I am one of the founders of Wingware. I'll be talking today about Wing IDE Professional. I'll give you a feature tour of Wing IDE 3.1 beta2, will show some of the new features in Wing 3.1, and will talk about some of our experiences developing Wing IDE over the years.

This talk is 30 minutes long and thus omits much that has been covered in previously given longer talks, such as a presentation on Wing 3.0 beta3 given some time ago in Boston.

About Wing IDE

- A commercial Python IDE

- We focus on Python

- Under development since 1999

- Sold since September 2000

- Runs on Windows, Linux, and OS X (w/ X11)

- Supports CPython 1.5.2 to 2.5, also Stackless

- Three product levels: Pro, Personal, and 101

Wing IDE is a commercial integrated development environment designed specifically for Python. Our strategy has been to focus on Python in order to provide the best possible solutions for Python programmers. Wing has been under development since 1999, with the first product sales in Sept of 2000.

Wing runs on Windows, Linux, and on OS X where it is currently an X11 application. The sources have also been compiled on Solaris, FreeBSD, and even the PlayStation3 but no binary distributions exist for those platforms.

Wing supports CPython 1.5.2 through 2.5 and also Stackless Python. You can also use much of Wing's functionality w/ IronPython and Jython, but the debugger currently does not support the .NET and Java VMs.

There are currently three product levels of the IDE: Professional, which is the full-featured edition. Personal, which is a low-cost alternative with a subset of the features. And 101, which is free, heavily scaled back, and was designed for teaching introductory programming courses. See our website for a feature comparison matrix and pricing among other information.

This talk focuses on Wing IDE Professional.

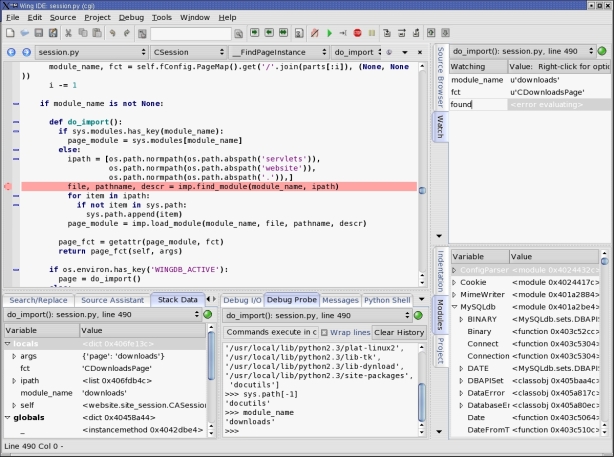

Wing IDE Demonstration

See the recorded talk or watch our screencasts or download and try out the Wing tutorial in the Help menu.

If you're reading this as a handout, you may want to try out Wing now by using the Tutorial from the Help menu. This demonstration will cover:

* Overall layout: Panels show/hide, tools menu

* Tutorial and How-Tos in Help menu

* Prefs: Keyboard personality, tab key, windowing mode, many others

* Setting up project: Add directory, Project Properties (python,

environment, revision control, unit testing, zope/plone)

* Editing

* Syntax highlighting

* Auto-completion, source assistant

* Index menus, browser, goto definition

* Open from Project and Find Symbol (new in 3.1)

* Inline snippets/templates (new in 3.1)

* Search interfaces

* Testing

* Supports unittest, nose, and doctest (latter two new in 3.1)

* Configuring tests

* Running tests

* Debugging tests

* Debugging

* Breakpoints (setting, types, breakpoint tool)

* Starting

* Looking around: Stack data, call stack, watch tools

* Debug Probe

* Launching process from outside Wing

* Other stuff (show briefly or just mention)

* OS Commands

* Bookmarks

* Indentation tool

* Extension scripting (e.g. pylint)

See also the available screencasts that introduce Wing IDE's functionality.

Other New Features in 3.1

- Debugging into zip files and zipped eggs

- doctest and nose unit test support

- pkg_resources name space merging for eggs

- Word list driven autocompletion in non-Python files

In the demo I showed some of the new features in Wing 3.1: quick selection of files in the project or symbols in the current file by typing fragments and inline code snippets in the auto-completer.

Other new features in Wing 3.1 note covered in the feature tour are support for debugging code that's stored in zip or egg files, doctest and nose unit testing support, support for name space merging via pkg_resources, which is often used by eggs and setuptools, and poor man's autocompletion in non-Python files.

Developing Wing IDE

- Written in Python (84%) and C (15%)

- Total Physical Source Lines of Code = 137,488

- Plus 5K lines of Python for build control

- Developed, tested, and debugged with itself!

Wing is written in Python and C. The line counts here were done using sloccount, which counts physical lines of code omitting blank lines and comments. About 85% of the code base is in Python, with the performance intensive parts in C. We try to write as little C as possible, and would probably write even less if we were doing this today.

These figures omit our custom build control system, which is mostly Python, about another 5K lines.

Writing, testing, and debugging Wing with itself is an important part of our quality control strategy. Self-use is one of the reasons open source tends to be of high quality. This should almost be a requirement for all programmers.

Based on Open Source

- 1.7 million lines of 3rd party source built into dist

- GTK and PyGTK for the GUI

- Scintilla for source editor

- Docutils for documentation

- Etcetera -- see About box

- Selling closed source built over open source, not support

- Limits choice of licenses (no GPL, but LGPL works)

Another thing not included in the previous slide's statistics is the 1.7 million lines of 3rd party source code that we build into Wing. We use and contribute to a lot of open source, and this has been important to our ability to concentrate on the IDE-specific functionality.

The size of this code is significant but not actually a surprizing given that we ship almost everything that supports the GUI with Wing to avoid dependencies and so Wing "just works" out of the box.

We've put perhaps a year full time into GTK and PyGTK, months into Scintilla, and for the rest we are mostly just users. See Wing's About box and manual for a complete list of the modules, authors, and license information.

For a long time, and certainly when we started out, the model we'ld hear about most often for doing business on an open source substrate was to give away the software but to sell support. Based on our experiences, we believe this would never work for an IDE, but it does work to layer a proprietary product onto open source and everyone benefits because time is put into the open source code by the commercial users.

Since we layer a proprietary product on open source, we can't use all open sources licenses. For example, we can't use anything GPL because of the "viral" terms of the license, but LGPL is fine as well as MIT, BSD, and most others.

Experiences with GTK and PyGTK

- Positives:

- Write once works anywhere (one widget impl)

- Signal model

- Descending from C "classes" in Python

- Easy to hand-code GUIs -- or build models

- Good asynchronous support (we avoid threads!)

- Negatives:

- Hard to build and ship GTK yourself

- Need to ship w/ GTK even on Linux (binary compatibility)

- Not native on OS X, requires X11 (for now)

- Not really native on Windows (but close)

As mentioned on the previous slide, we chose GTK for our GUI. This was done in 1999, and we've hardly looked back so we're not in a position to offer a point by point comparison with toolkits such as wxPython, Tkinter, and PyQt. However, I can talk a bit about our experiences with GTK since we're often asked about choice of GUI toolkit.

GTK is really good at "write once works anywhere" and by virtue of PyGTK and Python this even means we can distribute identical Python object code for the GUI in a cross-platform way (it runs against GTK compiled for each platform, of course). We've put significant time into GTK but it was a worthwhile investment that makes our day to day development much easier.

We also like GTK's rich signal model, which makes it very easy to hook functionality up to the GUI. It's also the basis for how C is used to write "classes", which via PyGTK can easily be descended from and overridden in Python. GTK has at its core a decent asynchronous task framework that's used to service the GUI and also can be used to simultaneously service network connections or run periodic tasks. We make heavy use of this, as Wing is entirely based on the asyncronous model rather than threading (more on this later).

Overall GTK and PyGTK's bindings are designed in a way that makes it quite easy to write GUIs either by hand in code, or to write code that builds GUIs based on models. We don't use a GUI builder but we do use some tools we developed to generate parts of the GUI automatically from data models and GUI hints. For example, Wing's preferences and project properties are generated that way.

Things we don't like so much about GTK include that it's very hard to build and ship GTK, but we do need to ship it with the app even on Linux because binary compatibility between GTK versions is sometimes an issue. We try very hard to make Wing "just work" (for the customer, and to keep support manageable) and shipping with GTK included reduces the risk of environment-specific problems. On Linux, --system-gtk on the command line can be used to override our internal GTK and use the system-provided one instead, and this often works.

Another significant issue is that GTK isn't native on OS X and requires an X11 Server. It works pretty well but native would be better. There's work on this and Gimp (also a GTK app) runs native on OS X. However, we guestimate it would take us a year of effort to get it working well. Wing uses more and different GTK functionality from other GTK apps, as we found out on Windows where lots of bug fixing was needed.

GTK also isn't really entirely native on Windows, but it's very close now and complaints have become relatively rare. In fact, we often have customers on Windows that mistake the GUI as having been written with wxPython.

Async not threads

- Tasks are split up into small units, interleaved with the GUI

- Context switch is well-defined (in event loop)

- Effort to split up tasks is less than effort to debug threads

- Works nicely with generators (yield after each task portion)

- Not using Twisted (GTK provides the mainloop)

Wing uses asynchronous tasks rather than threads to get its work done. We split up background tasks like source analysis into small units that run interleaved with the event loop. This is a big time saver for us. The time we spend splitting up tasks into small units is much less than the time it would take to track down complex threading bugs. Async is generally easier to manage because the context switch is much more predictable.

With generators it's really easy to do break a loop into units as in the trivial example above, and hook these into the GTK mainloop.

We're not using Twisted because GTK provides what we need, so it may not provide much added value in our case. But we hear it is wicked cool for other things.

Optimization or lack thereof

- We write all new code in Python

- Slow? Turn off brain, turn on profiler (hotshot)

- Try to optimize in Python

- Write small bits in C (not whole modules)

- Recognize C code can also be a bottle neck

- Have not used pyrex (maybe we should)

- Slightly afraid of psyco

I've been trying to highlight how we do things in light of our critical need to save time. We learned the hard way how best to write code that is "fast enough" in Python. Initially, we wrote any module we thought needed to be super-fast (like the debugger core and source code analysis engine) entirely in C. This was a mistake. Instead, we've learned to write in Python, optimize only what the profiler (hotshot) reveals as slow, and try to do that only in Python. As a last resort, we write small bits in C. We managed to do that with the search capability, some file I/O code, and some object life cycle stuff that ended up being performance critical. It's much easier to maintain than the pure C code.

Don't assume that performance issues are necessarily in your Python code. Sometimes C code can be a bottle-neck too. We sometimes have this problem, e.g. building large menus in GTK has been an issue.

We've not used pyrex though it looks like a good solution. I suppose we're just old salts and writing a few bits of extension module is too easy... although this is an area where we may be kidding ourselves and are not working as efficiently as we could.

Psyco is a bit problematic. It crashes Wing when in full optimization mode, or at least did some years ago when we tried it. We prefer to keep Wing as stable as possible, and it may not help much anyway since so much of the time in Wing is actually spent in C code and not in the relatively thin layer of Python that we wrote ourselves.

Debuggers: not just for bugs

- Design and try out code in context of the run state

- Run to breakpoint or conditional breakpoint

- Write code fragments in Debug Probe

- Auto-completer and source assistant show actual runtime state

- Try out code right away

- Watching code run helps in code learning

- Find out how something gets invoked

- Understand datastructures

- Watch dynamic code in action

- "Now Zope makes sense!"

The debugger also works well as a code learning tool, even when no bugs are present. It's the fastest way to understand how code is being invoked, what datastructures actually contain at runtime, and how dynamic or tricky code works. We often hear from people using Wing's debugger along with the source browser to decipher Zope's internals.

To add a new feature, it's often easiest to place a breakpoint in the code to be edited, run to the breakpoint, and design the new code in Wing's Debug Probe. The auto-completer and source assistant, which key off actual runtime state in this case, will make it easier to design the correct code quickly, even in unfamiliar territory or in complex code, and then try it right away.

Q&A

Thanks for coming!

For more information, please email support@wingware.com.